Stories of Strength:

Mark Belenchia

Stopping the Spiral

JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI – If anyone can comprehend the tumult of emotions that survivors of clergy abuse can experience, it’s Mark Belenchia. Mark describes an endless cycle of confusion, outrage, shame and betrayal as a vortex that he still struggles to escape from.

Mark was 12 in 1968 when a new priest joined his Catholic parish church in the small town of Shelby, Mississippi. Fr. Bernard Haddican was different from other priests, attending Little League baseball games in street clothes and inviting Mark and other boys to come to the rectory to watch NBA games together. Soon, he was offering beer, cigarettes, and pot to the boys and hosting sleepovers.

The first time Fr. Haddican touched him, Mark felt an out of body experience, like many abuse survivors often describe.

“I just rose up out of my own self,” Mark said, “and I watched what was going on from somewhere up on the ceiling.”

But as the abuse continued, Mark says that the worst part was the psychological games Haddican played on his victims. For example, Haddican made the boys go to confession and take the blame for sex acts he perpetrated on them.

“It stunted me physically,” Mark said. “I was just frozen, and didn’t grow for a long while.”

And while Mark never repressed what was happening, he also was skilled at masking his feelings. The ongoing abuse was a big secret that he was bound and determined not to reveal–after all, he was responsible for participating, according to the priest.

Eventually, Mark told his mother when he was 17. She brought Mark’s oldest uncle, a World War II vet, over to meet with Mark and they were shocked when that didn’t help him much.

So Mark grew older, making what he calls “horrible decisions” along the way. He didn’t want to tell his girlfriend about the abuse and broke up with her, because she wasn’t Catholic and her parents didn’t approve of him. Then he married his first wife “for all the wrong reasons,” but stayed married for 25 years. Towards the end of that marriage, the two of them sought counseling to work on their relationship in 1985, where he finally told her about the abuse. Both the counselor and his wife encouraged him to seek help and to confront the church.

The Vicar General at the time told Mark he didn’t know of any other reports and sent him to a nun for therapy, saying, “Mark, you will be in my prayers daily.”

Though Mark could see the vortex of emotions getting tighter, he also saw that the Catholic Church was manipulating him more and more.

“If I had to pinpoint a time that was pivotal for me, it was when I went to the bishop and he told me I was an anomaly, which I knew wasn’t true,” Mark says. “I thought I was crazy. I spent five years in bed, demons swirling.”

Furthermore, that nun counselor told him that suing the Catholic Church was the ultimate sin, so his effort to report Fr. Haddican just faded away.

What Mark then did was to learn about SNAP and call them for advice. He spoke with David Clohessy and pretended he knew a friend who was victimized. Those conversations went on for several years, although Mark admits that David probably saw right through him.

Things came to a head in 1998 when his mother was terminally ill with pancreatic cancer and one of his sons was struggling with addiction problems. His employer at the time, IBM, transferred him and he suffered a nervous breakdown when his mother died. While in the hospital, he attended group therapy where another patient’s misery encouraged Mark to put his arm around the other man and confess about being raped. The session abruptly ended and Mark was sent to tell his story to his psychologist, who happened to be an ex-priest.

Spurred on by the ex-priest, Mark took the bull by the horns and confronted the Catholic Church again. This time he found out that the diocese had known about his predator since 1961, so he sued them and the Church paid him $44,000.

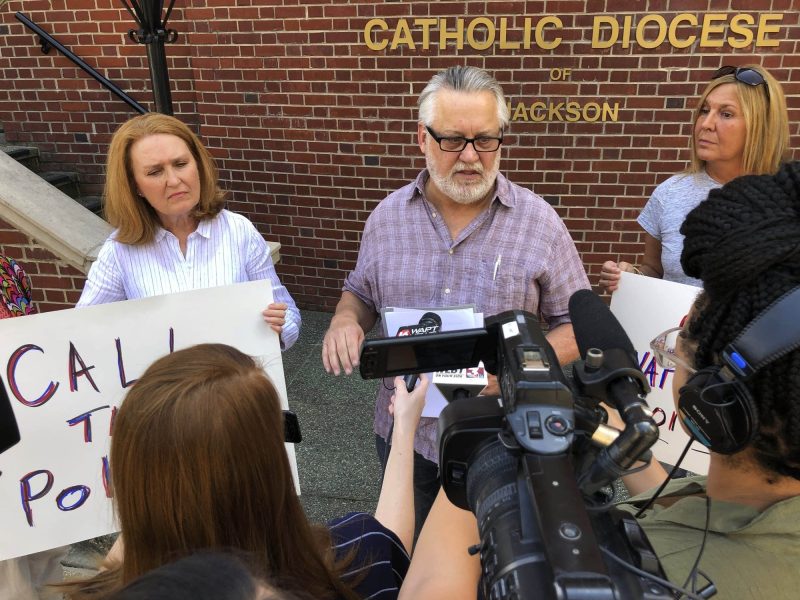

Nevertheless, Mark was still sick and took early retirement from IBM. But his languor didn’t last long. When Mark learned about two local brothers named Morrison who were also suing the Catholic Church, he went public with his own story. Afterward, 20 more people came forward, which galvanized him to start a SNAP chapter in Mississippi.

“I went to that office as though it were my job three days a week,” Mark said. “When SNAP came around, I got up to fight.”

He says the SNAP chapter gave him and the other survivors some power. Having their own website and representing a group with thousands of survivors meant that they were something to be reckoned with and carried a little more clout.

Over the years, Mark has been instrumental in bringing several cases forward, offering support and outrage, and demanding that outside authorities come in and investigate cases such as when three brothers named Love reported that they were molested by Franciscan friars in the 1990s. And his support extended beyond the Catholic Church as well. In two separate cases, when a Baptist minister and a Methodist minister in Mississippi were convicted of abuse, Mark was involved. And when a young man in Greenwood, Mississippi came forward with his report of recent abuse, Mark reached out to an AP investigative reporter for help. Michael Rezendes, a former Boston Globe reporter, who was part of the ‘Spotlight’ team that broke open the whole story in Boston which brought down Arch-Bishop Cardinal Bernard Law, came south and helped find a “missing” Franciscan monk whom the Catholic Church had pulled out of Mississippi and sent to Wisconsin to teach 9th graders.

“We finally got him arrested and put him in prison,” said Mark. “But this is tough stuff. I was out front and fired up but getting worn out.”

He explains that he’s glad he was able to help some people and continues to take strength from that spirit of fighting.

“It gave me a lot of fortitude to move forward,” Mark said, explaining that it’s helped him tremendously, at the same time that it has had profound ripple effects for him.

He’s still suffering from Complex PTSD and undergoes therapy once a week.

That doesn’t mean he’d ever give it up, however. Instead, he says, “My new way of handling things is to counsel folks to consider their motives and what’s going to help them.”

After a few conversations, he’s ready to ask, “Where do you want this to go?”

That’s his way to help them figure out which direction they want to go once they stop spinning and can begin their healing journey.