Stories of Strength:

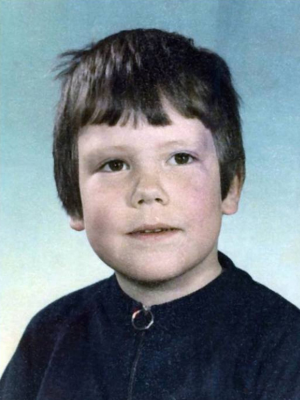

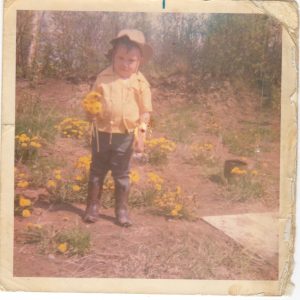

Nicholas Harrison

Lights. Camera. Action!

DELTA, British Columbia – As a professional stuntman, Nic Harrison attributes his career choice to the years he endured being attacked and abused in a parochial school in Canada’s British Columbia province.

From the age of five years old, he fought silently, not against bullying children, but against an entire administration of monsters running the school. Nic has published his awful tale in his book, “Safe Space: A True Story of Faith, Betrayal, and the Power of the Force,” and also as a play, “How Star Wars Saved My Life,” detailing the rigors of standing up time and again from where he’d been beaten and assaulted.

At heart, it’s a story of a working-class family in the small mill town of Prince George, where his parents chose to send their children to a Catholic school run by the Presentation Brothers for a better education. As so many children have found in other similar faith-based institutions, some of the staff had the worst of intentions for the student body: systematic grooming and ultimate long-term sexual abuse.

For Nic–and his half-sister he later learned–a childhood filled with loving attention and pancake breakfasts put together by a father who left early each morning for work as a welder was destroyed as soon as he set foot in the school. What started in kindergarten as punishment by strap in the hallway for misbehavior, gradually escalated to sexual assaults and regular beatings perpetrated by a cast of characters. From Brother Leopold, the principal, to several brothers who served as instructors, to Father Raynor, the priest of the cathedral at the school, on down to a lay female teacher, the staff meted out “punishment” to children, blaming the students for their heinous actions. To ensure none of the victims spoke about what was happening, the perpetrators told the children that their families would be murdered if they told anyone.

“It was a terrible burden to have as a child,” Nic says. “The entire time I’m going to believe that God would kill my family if I don’t comply.”

Fortunately for Nic, the abuse came to light when his mother noticed angry welts all over his legs one hot day when she insisted he wear shorts. At nine-years-old, Nic agonized over what to tell her. In his little boy logic, he decided that since he’d received this particular beating at the hands of a lay female teacher, then he could tell the truth. There wasn’t a special bond between God and a non-clergy member, he deduced, so his family wouldn’t be hurt.

In an instant, once he reported being beaten by an electrical chord with a heavy Bakelite plug, Nic was immediately pulled from the school, ending four years of torture. He said when his mother called the school, Brother Leopold begged her to keep Nic in school so they could continue to get funding.

“Mom yelled at him and called him a sick son of a bitch,” Nic recalls.

And that was the extent of his rescue at that point. Nic had the immediate support of his parents, for which he feels extremely lucky, but the damage was already done. While he patched together a life at the public school, he still didn’t feel safe, of course. As a way to protect himself, he limited his circle of acquaintances.

“Even now, I have very few people who are close to me, by choice, out of fear of being hurt,” he says.

Nevertheless, he was able to move forward to some degree. He studied at the London Academy of Performing Arts and went on to graduate school, earning both a master’s degree from the University of Victoria and a PhD from the University of British Columbia. He has worked as a writer, actor, director, swordsman, fight director, playwright, and educator, currently serving as an instructor at Capilano University. But Nic attributes his accomplishments to the trauma, saying he’s left with a constant need for reassurance and acceptance.

“This will show people that I’m good, that I’m worthy,” he explains.

And as for making social connections, he did marry and have two children. But as his relationship with his first wife began to look serious, Nic undertook intensive therapy to make sure he didn’t become an abuser.

In that effort, he found a therapist who encouraged him to report what had happened to him at Sacred Heart Elementary between 1973 and 1977. But when Nic tried to file a police report in 1997, he was turned away from two authorities: the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Richmond, because that wasn’t where the abuse happened, and in Prince George, where the school is located, because too much time had passed.

Blocked from criminal prosecution, his therapist suggested he pursue civil action, so he filed a lawsuit against the school and the diocese. But that effort did little to help Nic heal and trying to find other victims at the time was hard. He explains that his civil action occurred long before the movie “Spotlight” came out, which raised the public’s awareness and opened avenues for more people to tell their stories.

“People made fun of me at the time,” Nic said. “They made jokes about altar boys and my parents were ridiculed by our neighbors. No one wanted to talk about it.”

In 2010, Nic joined the Vancouver chapter of SNAP, and says he finds it helps to speak up, to know that there are other survivors out there who know what he’s gone through.

“We belong to a curious club, us survivors,” he says. “There’s a sense of fraternity, a sad fraternity. There is a strength in coming together and saying that that was wrong.”

It wasn’t until 2021 that he refiled the lawsuit, and half a dozen other survivors came out at that time as witnesses against the school and the same perpetrators.

But the saga is still ongoing. Two of the defending parties–the school and the OMI–settled, but the Presentation Brothers who ran the school declared bankruptcy. Pursuing accountability against those defendants is ongoing. While his story has been reported in national and international media, Nic doesn’t yet feel better or “strong” as others have called him.

“I still deal with it every day,” Nic says. “I don’t think of myself as a strong person. I guess I was resilient, but it was a contributor to my marriage dissolving. I’ve been speaking up to try to heal the child within myself. Letting myself know that I’m not to blame.”

And even after all this time, Nic still struggles. He imagines himself as a living example of the Japanese art of Kintsugi, where broken pottery is fitted back together with gold. He’s still working to make a new creation that is purportedly more beautiful because of its brokenness.

Now, Nic is newly engaged, living with his fiancee and both of their daughters, which he never thought possible. When his fiancee read his book, her deep concern showed him that he still has much to learn.

“Learning to accept love is a big deal,” Nic says. “And that I don’t have to do everything; that I can share in wins and losses, that it’s so much easier than doing it all alone. I’ve found a true safe space.”

It’s a good thing for Nic because the fight for justice still continues. His current litigation against the Presentation Brothers of Ireland, who ran the school, and two deceased members — Dennis O’Mahoney, a school principal known as Brother Leopold, and Vincent James, a teacher known as Brother Paschal, was delayed by an “11th-hour” bankruptcy declaration in November.

While Nic vows to continue to fight and to heal, he also says, “Although I have come to peace and feel somewhat vindicated against two of the three entities that I took on, this is not what defines me anymore. I don’t have to keep sounding the alarm bell any more.”

But he remains steadfast in the need to persevere and find solace in togetherness. He says that only through community are we strong and that sharing our stories builds our strength.

“I will gladly stand up and testify for anyone else who needs it to help others in this terrible fraternity of victims.”

SNAP Survivors Network is the world’s oldest and largest community of survivors of clergy and institutional sexual abuse. Through public action and peer support, SNAP is building a future where no institution is beyond justice and no survivor stands alone. Our global community works to end sexual abuse in faith-based organizations by transforming laws, institutions, and lives. Please support SNAP’s vital mission.